Rimbaud’s epic prose suite, Les Illuminations, can be visually adapted in a way that retains the symbolic core of the poetic form, expands the levels of meaning and illusion, and is congruent with the aims of both the poet and the artistic movement he inspired.

Introduction: Context and Methodology

It has become a truism that the various modes of artistic expression, from poetry to painting, dance, theatre and film, are somehow related or share something in common. The precise nature of their interrelation and how it impacts the feasibility of adaptation and exchange of ideas between artistic modes is not well understood. The most obvious examples of cross-disciplinary approaches to solving the same artistic problems can be found in the works of Surrealists, and the Proto-Surrealists who planted the seeds of their focus. Characteristic of Surrealism is the “incredible cross-pollination of visual art, film and literature” (Indiana University-Purdue University Fort Wayne 2007) and similar ideas are expressed in surrealistic terms in different modes. This may be due to the fact that “surrealistic terms” are intentionally non-discursive (even ideologically anti-rational) so they present mainly to our perceptive rather than logical powers (Hedges 1983). Surrealism is also uniquely centred around the broad aims of exploring the inner world of our subconscious minds, which does not lend itself logically to one medium over another because our internal worlds include experiences and illusions composed of all types of sense data both real and imagined.

Andre Breton delineated the ideology of Surrealism, but he credited Arthur Rimbaud with creating Surrealism’s “Grande Oeuvre” of “multiplying the ways of penetrating the deepest layers of the mind” (Bays 1964). Rimbaud lived and worked fifty years before the formalized movement, but he has been called the “father of surrealism” (Bays 1964) because it was his creative innovation that “laid the basis for a new opening out into the supernatural and surreal world” (Fowlie 1993, p. 23), and bloomed into a cross-modal art semantic that is active to this day. Rimbaud’s prose work Illuminations has made ripples in other artistic modes, having inspired a musical adaptation by Benjamin Britten, prints by Ferdinand Leger (Fig. 1), and a play (later to become a film starring Leonardo DiCaprio as Rimbaud) about the poet’s life during the writing of Illuminations (Fowlie 1949). Of these examples, only Britten’s orchestral piece could be called an adaptation because it contains the poems and their associated meanings while also expanding the symbol (Langer 1967). Illuminations is suitable for visual adaptation that expands the symbol similarly to Britten’s musical formation. It is a poetic work that exemplifies the surrealistic and symbolist use of language (Fowlie 1946), which implies as much as it states (Langer 1967, p. 154) serving as a “catalyst to imagination”(Hedges 1983) and treating imaginary and inner worlds with religious seriousness (Langer 1974, p. 175). Guided by Susanne Langer’s philosophical framework, in light of recent scientific research, I will examine the feasibility and methodology of a visual adaptation of the poetic work Illuminations and whether the addition of images could strengthen the imaginative “catalyst” in the poetry.

Andre Breton delineated the ideology of Surrealism, but he credited Arthur Rimbaud with creating Surrealism’s “Grande Oeuvre” of “multiplying the ways of penetrating the deepest layers of the mind” (Bays 1964). Rimbaud lived and worked fifty years before the formalized movement, but he has been called the “father of surrealism” (Bays 1964) because it was his creative innovation that “laid the basis for a new opening out into the supernatural and surreal world” (Fowlie 1993, p. 23), and bloomed into a cross-modal art semantic that is active to this day. Rimbaud’s prose work Illuminations has made ripples in other artistic modes, having inspired a musical adaptation by Benjamin Britten, prints by Ferdinand Leger (Fig. 1), and a play (later to become a film starring Leonardo DiCaprio as Rimbaud) about the poet’s life during the writing of Illuminations (Fowlie 1949). Of these examples, only Britten’s orchestral piece could be called an adaptation because it contains the poems and their associated meanings while also expanding the symbol (Langer 1967). Illuminations is suitable for visual adaptation that expands the symbol similarly to Britten’s musical formation. It is a poetic work that exemplifies the surrealistic and symbolist use of language (Fowlie 1946), which implies as much as it states (Langer 1967, p. 154) serving as a “catalyst to imagination”(Hedges 1983) and treating imaginary and inner worlds with religious seriousness (Langer 1974, p. 175). Guided by Susanne Langer’s philosophical framework, in light of recent scientific research, I will examine the feasibility and methodology of a visual adaptation of the poetic work Illuminations and whether the addition of images could strengthen the imaginative “catalyst” in the poetry.

Susanne Langer’s philosophy provides a theoretical context for the relationship between various arts;

Art is essentially one . . . the symbolic function is the same in every kind of artistic expression, all kinds are equally great, and their logic is all of one piece, the logic of non-discursive form (1967, p. 103).

Langer’s philosophies of art and mind centre around the proposition that symbolic transformation is a fundamental “pre-rationative” process of the human mind and the method by which we make ideas out of vague feelings and sense impressions (below the level of speech) (Langer 1974, p. 41-42, 144). A symbol is defined as “any device whereby we are enabled to make an abstraction” (Langer 1967, p. xi) and what art in all modes and mediums creates are “forms symbolic of human feelings” (Langer 1967, p. 40). Within this conceptual structure language can be seen as a symbolism, or a system of symbols, usually arranged according to grammar and syntax and organized in relation to laws of discursive reason (Langer 1967, p. 369). In contrast, an artwork is a single indivisible and highly articulated non-discursive symbol that is not a proxy for what it conveys but “has” or embodies the objectification of human feeling in its total form (Langer 1967, p. 369). This can be thought of as presentational symbolism (because it presents to our perception) and the meanings of symbolic elements are understood through the whole and “their relationships within the total structure” (Langer 1974, p. 97).

This is a departure from the usual way of describing iconographic functions of art symbols and results in a deeper semantic of holistic non-discursive symbols that “negotiates insight, not reference” and “does not rest upon convention, but motivates and dictates conventions” (Langer 1967, p. 22). The objectification of forms of feeling is perceived as a sense of virtual “livingness” that is an illusion created when forms follow the pattern of inner life (Langer 1967, p. 82). Such forms are “congruent with the tensions and resolutions, rise and fall, of emotions” (Langer, cited in Reese 1977), and the “morphology of life – forms of growth, flowing, excitement, calm” (Langer, cited in Hart 1997). From Langer’s perspective, this artistic “symbol of sentience” is the core creation of arrangements made using tones or colours as well as gestures and the non-discursive poetic uses of language (Langer 1967). Her idea that artistic modes are related through an emotional core is supported by recent studies at Berkeley that show subjects to have cross modal matching between colours and music that are mediated by emotion (in non-synesthetes), resulting in a high correlation between emotional ratings of music and colours (UC Berkeley 2012). It follows logically that different techniques and materials could be used to create non-discursive art symbols in different modes that have at least broadly similar emotive symbolism (import). Furthermore, the qualitative character of an art symbol could be expanded or reinforced by adding levels of illusions from multiple modes (Langer 1967). If the Berkeley subjects were simultaneously presented with an emotive piece of music and a Rothko of the emotionally correlated colour, the import of the symbol would likely be more powerful or apparent than their reaction to the colour or sound alone.

Art is essentially one . . . the symbolic function is the same in every kind of artistic expression, all kinds are equally great, and their logic is all of one piece, the logic of non-discursive form (1967, p. 103).

Langer’s philosophies of art and mind centre around the proposition that symbolic transformation is a fundamental “pre-rationative” process of the human mind and the method by which we make ideas out of vague feelings and sense impressions (below the level of speech) (Langer 1974, p. 41-42, 144). A symbol is defined as “any device whereby we are enabled to make an abstraction” (Langer 1967, p. xi) and what art in all modes and mediums creates are “forms symbolic of human feelings” (Langer 1967, p. 40). Within this conceptual structure language can be seen as a symbolism, or a system of symbols, usually arranged according to grammar and syntax and organized in relation to laws of discursive reason (Langer 1967, p. 369). In contrast, an artwork is a single indivisible and highly articulated non-discursive symbol that is not a proxy for what it conveys but “has” or embodies the objectification of human feeling in its total form (Langer 1967, p. 369). This can be thought of as presentational symbolism (because it presents to our perception) and the meanings of symbolic elements are understood through the whole and “their relationships within the total structure” (Langer 1974, p. 97).

This is a departure from the usual way of describing iconographic functions of art symbols and results in a deeper semantic of holistic non-discursive symbols that “negotiates insight, not reference” and “does not rest upon convention, but motivates and dictates conventions” (Langer 1967, p. 22). The objectification of forms of feeling is perceived as a sense of virtual “livingness” that is an illusion created when forms follow the pattern of inner life (Langer 1967, p. 82). Such forms are “congruent with the tensions and resolutions, rise and fall, of emotions” (Langer, cited in Reese 1977), and the “morphology of life – forms of growth, flowing, excitement, calm” (Langer, cited in Hart 1997). From Langer’s perspective, this artistic “symbol of sentience” is the core creation of arrangements made using tones or colours as well as gestures and the non-discursive poetic uses of language (Langer 1967). Her idea that artistic modes are related through an emotional core is supported by recent studies at Berkeley that show subjects to have cross modal matching between colours and music that are mediated by emotion (in non-synesthetes), resulting in a high correlation between emotional ratings of music and colours (UC Berkeley 2012). It follows logically that different techniques and materials could be used to create non-discursive art symbols in different modes that have at least broadly similar emotive symbolism (import). Furthermore, the qualitative character of an art symbol could be expanded or reinforced by adding levels of illusions from multiple modes (Langer 1967). If the Berkeley subjects were simultaneously presented with an emotive piece of music and a Rothko of the emotionally correlated colour, the import of the symbol would likely be more powerful or apparent than their reaction to the colour or sound alone.

Illuminations and Rimbaud Within Langer’s System of Symbolism

Rimbaud writes himself into the centre of a cosmic poetic epic in which symbolic transformation occurs at multiple levels (Fowlie 1946; Langer 1974). The indivisible non-discursive/presentational symbol of each poem in Illuminations contains within it other symbolic materials as its elements, and the semblance of epic narrative is created by the work as a whole. Illuminations can be broadly summarized as a poetic work in which Rimbaud “narrate[s] the poem of a spiritual quest which never defines itself” (Fowlie 1946, p. 35). His themes mainly deal with “the fate of the genius and the method of the artist” in poetic terms that he calls, “alchemie du verbe” (Fowlie 1946, p. 109; Rimbaud, cited in Hedges 1983). As elements, he employs historically charged symbols borrowed and repurposed from nature mythology, alchemy, religion, fairy-tale, and legend (Langer 1974; trans. Ashbery 2011). By casting himself as the visionary narrator and explorer on this “symbolic voyage,” Rimbaud facilitates his own metamorphosis into mythological figure and culture-hero (Fowlie 1946, p. 34; Langer 1974 p. 181). The life and character of the artist become intertwined with the symbolism and magic of his literary incarnation, causing his legend to supersede reality (Fowlie 1993).

Rimbaud breaks with the 18th century traditions of discursive reason and classical rhyming verse, and his rebellious eccentricity aligns him with the modern epic hero, defined by Wallace Fowlie as “the artist who often loses the thread of his life and whose voyage-symbols . . . are ways of self-knowledge,” the romanticized genius (Fowlie 1946, p. 35). Within Langer’s (1974, p. 185) framework, the poet and his poetic personage merge into “culture-hero,” a human story hero who has been abstracted to represent “man” as a tribe, “overcoming the superior forces that threaten him.” The Rimbaudian visionary explorer of Illuminations is a culture-hero in a non-discursive epic because the poetic form abstracts the narration in such a way that the voyage is presented to perception as our own experience and journey (Langer 1974), as the abstracted journey of “man” through a cosmic superreality where “every natural object ends by symbolizing human life” (Fowlie 1946, p. 104). This cosmic symbolism is characteristic in Langer’s view of the mythological mode, which is typified by “no fixity; either of form or meaning” and the “condensations of numberless ideas” (Langer 1974, p. 196), and the “all-inclusive story of the world” embodied in the epic (Langer 1967, p. 305). The accretion of associations and emotionally charged impressions that accumulate from reading Illuminations as a whole give it the semblance of epic narrative (Langer 1967, ch4). This happens because the poems condense into fleeting memories of virtual experiences (Langer 1967, ch15), and even though there is no logical plot or consistent characters, it is characteristic of the functioning of our minds that the first thing we do with virtual impressions of this sort is to connect them together to “envisage a story” (Langer 1974, p. 145).

Rimbaud breaks with the 18th century traditions of discursive reason and classical rhyming verse, and his rebellious eccentricity aligns him with the modern epic hero, defined by Wallace Fowlie as “the artist who often loses the thread of his life and whose voyage-symbols . . . are ways of self-knowledge,” the romanticized genius (Fowlie 1946, p. 35). Within Langer’s (1974, p. 185) framework, the poet and his poetic personage merge into “culture-hero,” a human story hero who has been abstracted to represent “man” as a tribe, “overcoming the superior forces that threaten him.” The Rimbaudian visionary explorer of Illuminations is a culture-hero in a non-discursive epic because the poetic form abstracts the narration in such a way that the voyage is presented to perception as our own experience and journey (Langer 1974), as the abstracted journey of “man” through a cosmic superreality where “every natural object ends by symbolizing human life” (Fowlie 1946, p. 104). This cosmic symbolism is characteristic in Langer’s view of the mythological mode, which is typified by “no fixity; either of form or meaning” and the “condensations of numberless ideas” (Langer 1974, p. 196), and the “all-inclusive story of the world” embodied in the epic (Langer 1967, p. 305). The accretion of associations and emotionally charged impressions that accumulate from reading Illuminations as a whole give it the semblance of epic narrative (Langer 1967, ch4). This happens because the poems condense into fleeting memories of virtual experiences (Langer 1967, ch15), and even though there is no logical plot or consistent characters, it is characteristic of the functioning of our minds that the first thing we do with virtual impressions of this sort is to connect them together to “envisage a story” (Langer 1974, p. 145).

Adapting Poetry to Another Artistic Mode:

Swallowing and Transforming the Symbol

Langer criticizes the traditional methods of interpreting poems in “non-poetic” or “less poetic terms than the thing interpreted” (Langer 1974, p. 234), implying that poems can be interpreted or explored more successfully through non-discursive means because discursive language cannot reflect the natural forms of feeling (Langer, cited in Reese 1997). To Langer (cited in Hart 1997), poetry is the only use of language that can preserve its original mythic power and creative power over logic which is probably especially true of anti-rational surrealist poetry that expressly aims to restore the vitality that language had during its creation, “at the birth of the signifier” (Breton, cited in Bays 1964). Poetic use of language creates an expressive core that cannot be made more understandable through discursive description or analysis (Langer 1967). Langer (1967, p. 157) proposes that, “every poem for music must have . . . an expressive core,” and I think the same is necessary of poems suitable for visual adaptation. This type of adaptation can be understood through Langer’s (1967, p.157, 164) principle of assimilation “whereby one art ‘swallows’ the products of another” because “a work can exist in only one primary illusion.” Accordingly, Britten’s Illuminations is a musical adaptation that transforms the poetic material into auditory elements or lyrics, and a visual adaptation would similarly “swallow” the poems and transform them into visual elements within the virtual picture space.

Rimbaud was part of the Symbolist movement of French poetry, which has been described as pursuing the “resanctification of human speech,” a goal that was later taken up by the Surrealists (Fowlie 1993, p. 66). This special genre of poetic prose meets Langer’s criteria for text that is particularly suited for transformation into other modes. She specifically mentions the poetry of Verlaine (Rimbaud’s creative mentor and lover) as good text for music because of the amount that is implied;

All their potentialities are still there and are emphasized by the ironically casual form. Consequently the poetic work can dissolve again at the touch of an alien imaginative force, and the beautiful, overcharged words . . . can motivate entirely new expressive forms, musical instead of poetic (Langer 1967, p. 154).

A capable composer can transform the right verbal material “sound, meaning, and all” into musical elements (Langer 1967, p. 150). Although music has no literal meaning, it can “present emotive experience through global forms that are as indivisible as the elements of chiaroscuro” (Langer 1974, p. 232). “Music can reveal the nature of feelings with a detail and truth that language cannot approach” (Langer 1974, p. 235) because auditory characters sound the way moods feel (Langer 1974, p. 245). Since language can present to both sight and hearing, a poem can be subsumed within any artistic mode that can carry its poetic core (which is inseparable from the words) within an illusion that is presented to our eyes and/or ears.

The poet uses discourse to create an illusion, a pure appearance, which is a non-discursive symbolic form. The feeling expressed by this form is neither his, nor his hero’s, nor ours. It is the meaning of the symbol (Langer 1967, p. 211).

Therefore, any transformation or adaptation must allow the expressive symbolic core of the poem(s) to remain as intact as possible. The poem as a whole is the symbolic form; expressing vital experience through a pattern of sentience, so when poetry is translated linguistically, the product is related but new, “like the orchestral scoring of an organ fugue” (Langer 1974, p. 262). The material of prose poetry is discursive language, but the product and resulting form is not (Langer 1967, p. 297), so a word for word literal translation will not create exactly the same global pattern, which is its semblance of “virtual life” and main symbolic illusion (Langer 1967). The non-discursive poetic art symbol is inseparable from its particular arrangement of specific words, but it may be successfully transformed (through translation) into a new but related form, or adapted though lifting the whole art symbol into the illusion of a different symbolic mode (Langer 1967, ch10).

Rimbaud was part of the Symbolist movement of French poetry, which has been described as pursuing the “resanctification of human speech,” a goal that was later taken up by the Surrealists (Fowlie 1993, p. 66). This special genre of poetic prose meets Langer’s criteria for text that is particularly suited for transformation into other modes. She specifically mentions the poetry of Verlaine (Rimbaud’s creative mentor and lover) as good text for music because of the amount that is implied;

All their potentialities are still there and are emphasized by the ironically casual form. Consequently the poetic work can dissolve again at the touch of an alien imaginative force, and the beautiful, overcharged words . . . can motivate entirely new expressive forms, musical instead of poetic (Langer 1967, p. 154).

A capable composer can transform the right verbal material “sound, meaning, and all” into musical elements (Langer 1967, p. 150). Although music has no literal meaning, it can “present emotive experience through global forms that are as indivisible as the elements of chiaroscuro” (Langer 1974, p. 232). “Music can reveal the nature of feelings with a detail and truth that language cannot approach” (Langer 1974, p. 235) because auditory characters sound the way moods feel (Langer 1974, p. 245). Since language can present to both sight and hearing, a poem can be subsumed within any artistic mode that can carry its poetic core (which is inseparable from the words) within an illusion that is presented to our eyes and/or ears.

The poet uses discourse to create an illusion, a pure appearance, which is a non-discursive symbolic form. The feeling expressed by this form is neither his, nor his hero’s, nor ours. It is the meaning of the symbol (Langer 1967, p. 211).

Therefore, any transformation or adaptation must allow the expressive symbolic core of the poem(s) to remain as intact as possible. The poem as a whole is the symbolic form; expressing vital experience through a pattern of sentience, so when poetry is translated linguistically, the product is related but new, “like the orchestral scoring of an organ fugue” (Langer 1974, p. 262). The material of prose poetry is discursive language, but the product and resulting form is not (Langer 1967, p. 297), so a word for word literal translation will not create exactly the same global pattern, which is its semblance of “virtual life” and main symbolic illusion (Langer 1967). The non-discursive poetic art symbol is inseparable from its particular arrangement of specific words, but it may be successfully transformed (through translation) into a new but related form, or adapted though lifting the whole art symbol into the illusion of a different symbolic mode (Langer 1967, ch10).

Expanding the Art Symbol: Accumulation of Meaning, Reinforcing Metaphor, Paradox, and Nature Symbols

Making up our minds about a poem’ . . . We have to gather millions of fleeting semi-independent impulses into a momentary structure of fabulous complexity, whose core or germ only is given us in the words (I. A. Richards, cited in Langer 1967, p. 210).

Rimbaud and the surrealist writers produced poetic illusions using the formulative rather than the propositional powers of language (Hart 1997; Hedges 1983). Consequently, many of the poetic ideas (metaphorical meanings, paradoxes, moods, and nature symbols) can be presented to our formulative perception (to make us understand the idea) equally well through pictorial symbolism. A visual adaptation that subsumes the text and also reiterates its poetic ideas in images could expand the art symbol (Langer 1967, p. 242). It could echo and amplify the meanings of the poem potentially more than a musical adaptation (ironically) because pictures can contain sensuous emotional import as well as literal and representational significance, whereas music can only elaborate emotionally without literal objective reference (other than the text) to reinforce or explicate meaning (Langer 1967). In Illuminations, the semblance of cosmic epic relies on the mythological principle of condensation of meanings: multiple meanings, representative figures, and repetition instead of proof (Cassirer, cited in Langer 1967). Within this semantic, the poet is able to present a philosophical idea directly to our perception of its emotive and imaginative possibilities rather than presenting the idea discursively for debate (Langer 1967). An idea presented poetically cannot be negated, but it can be reinforced through non-discursive repetition and elaboration (Langer 1967). In other words, the poetic core can be given new power through the addition of illusions that add to accumulation and/or apparentness of meanings.

The reason that poetic symbols are best expanded through non-discursive means is the "pervasive ambivalence which is characteristic of human feeling" -- joy-melancholy and other paradoxes (Tillyard, cited in Langer 1967, p. 227). Opposites can be conceptually brought together as poetic ideas that reveal their connection; or visually, through the similarity of dynamic structure in faces showing pain and ecstasy for example. Discursive description can only “emphasize their separateness” (Langer 1967, p. 242). Every poetic work creates a virtual world peculiar to it in which “poetic facts” “occur only as they seem” (Langer 1967, p. 217, 223). So although poetic facts have no existence apart from values, their significance requires a spark of literal acceptance, of taking poetic statement as a “fact” of some order with meaning related to inner truths rather than measurable external realities. Rimbaud presents ambivalent paradoxical ideas so successfully that “atheists and Catholics, mystics and surrealists” can all find “doctrinal confirmation” in his work (Fowlie 1946, p. 39). The paradoxical nature of a character like the prince in Tale (the 3rd poem of Illuminations) who both violently destroys the genie he meets and is the genie, can be conceptually revealed through an ambiguous and metamorphosing visual form as clearly as it can be expressed poetically, and more easily than non-poetic language could express a similar idea.

There seems to be some consensus between Surrealists, Langer, and scientists that metaphor is a process for expressing and understanding new ideas, thereby increasing knowledge (Hedges 1983; Langer 1974; University of California Television 2008). Dr. Ramachandran (University of California Television 2008) describes metaphor as taking unrelated ideas and making a link using either words or pictures. He believes that metaphor is a fundamental principle of artistic “grammar” by which visual ideas are presented to us somewhere between perceptual and conceptual processing (University of California Television 2008). The “language universal” recently found by researchers at MIT suggests such linking may exist in all languages because they all create meaning by organizing associated words in close physical proximity within the sentence (O’Grady 2015). Langer (1974, p. 147) also views metaphor as central to art: “Metaphor is the law of growth of every semantic. It is not a development, but a principle.” She relates it to the “laws of imagination” and views it not as an intentional device, but as an inevitable growth resulting from “the power whereby language embraces a multimillion things; whereby new words are born and merely analogical meanings become stereotyped into literal definitions” (Langer 1967, p. 141). The meanings of words and other symbols are not static and metaphor creates “metamorphosis of its meaning,” so that words in poetry may “hover between literal and figurative,” and what begins as wild metaphor can change to almost literal meaning while carrying “a trace of every meaning it has ever had” (Langer 1974, p. 281-282). Surrealists similarly relate metaphor to their alchemical concept of metamorphosis, and they use it to combine disparate elements into poetic facts that Breton (cited in Hedges 1983) insists should be taken literally. The metaphors in Illuminations often have a literal sense that could be revealed or reinforced pictorially due to the cross-modal and pre-rational nature of metaphor. The qualities of Rimbaud’s metaphorical landscapes, for example the difference between a sea “which rose in layers above as in old engravings” and a “sea made of an eternity of hot tears” can be made apparent through pictorial techniques that take metaphorical qualities as literal and support if not express the same core poetic symbolism (trans. Ashbery 2011, p. 19, 27).

Illuminations uses the highly charged symbols of nature mythology, alchemy, religion, fairy-tale, and legend as its materials. Langer suggests that these symbols “are not bound to any particular words, nor even to language, but may be told or painted, acted or danced, without suffering distortion or degradation” (Sewell, cited in Langer 1967, p. 274). If a visual adaptation could denote these same symbols in accompaniment to the text, then the meaning of the art symbol, which is the presentation of the idea, could become more highly articulated. Images are “our readiest instruments for abstracting concepts from the tumbling stream of actual impressions” (Langer 1974, p. 145). Associated meanings are not “part of the import of poetry; they serve to expand the symbol” (Langer 1967, p. 242), and some of these associated meanings and the emotional import of iconographic symbols could be simultaneously presented through images that contain the poems. Poetry creates virtual events that are simplified in order to be more fully perceived (Langer 1967, p. 212), and images similarly simplify forms and selectively emphasize what strikes the artist as significant (Langer 1967; University of California Television 2008). A caricature can be easier to recognize than a photograph of a person because our brains are sensitive to deviations from the norm, to artistic exaggeration (University of California Television 2008; Livingstone 2002, p. 204). Symbols like rainbows, which appear numerous times in Illuminations, carry traces of multiple meanings; scientifically they are one of the most striking naturally occurring “virtual objects,” in nature mythology they are treated as elusive maidens, and in alchemy they represent rebirth with each colour being a stage in the process to spiritual perfection (Langer 1967, p. 49; Bays 1964). These meanings and more are attached to the word as well to the image of a rainbow, but only an image can symbolize a rainbow while also emphasizing the characteristic(s) of significance, whether it is the transient elusive quality, the brilliance of the hues, or the weather conditions of sun and rain that cause the illusion. Images can bring forth the sensuous character of words through representation with emphasis, what Dr. Ramachandran (University of California Television 2008) calls, “deliberate distortion for the purpose of hyperbole” and Langer (1967, p. 51) describes as abstracting physical forms to make them clearly apparent. These sensuous qualities and aesthetic surface are “in the service of its vital import” which is the emotional meaning of the art symbol (Langer 1967, p. 59).

Rimbaud and the surrealist writers produced poetic illusions using the formulative rather than the propositional powers of language (Hart 1997; Hedges 1983). Consequently, many of the poetic ideas (metaphorical meanings, paradoxes, moods, and nature symbols) can be presented to our formulative perception (to make us understand the idea) equally well through pictorial symbolism. A visual adaptation that subsumes the text and also reiterates its poetic ideas in images could expand the art symbol (Langer 1967, p. 242). It could echo and amplify the meanings of the poem potentially more than a musical adaptation (ironically) because pictures can contain sensuous emotional import as well as literal and representational significance, whereas music can only elaborate emotionally without literal objective reference (other than the text) to reinforce or explicate meaning (Langer 1967). In Illuminations, the semblance of cosmic epic relies on the mythological principle of condensation of meanings: multiple meanings, representative figures, and repetition instead of proof (Cassirer, cited in Langer 1967). Within this semantic, the poet is able to present a philosophical idea directly to our perception of its emotive and imaginative possibilities rather than presenting the idea discursively for debate (Langer 1967). An idea presented poetically cannot be negated, but it can be reinforced through non-discursive repetition and elaboration (Langer 1967). In other words, the poetic core can be given new power through the addition of illusions that add to accumulation and/or apparentness of meanings.

The reason that poetic symbols are best expanded through non-discursive means is the "pervasive ambivalence which is characteristic of human feeling" -- joy-melancholy and other paradoxes (Tillyard, cited in Langer 1967, p. 227). Opposites can be conceptually brought together as poetic ideas that reveal their connection; or visually, through the similarity of dynamic structure in faces showing pain and ecstasy for example. Discursive description can only “emphasize their separateness” (Langer 1967, p. 242). Every poetic work creates a virtual world peculiar to it in which “poetic facts” “occur only as they seem” (Langer 1967, p. 217, 223). So although poetic facts have no existence apart from values, their significance requires a spark of literal acceptance, of taking poetic statement as a “fact” of some order with meaning related to inner truths rather than measurable external realities. Rimbaud presents ambivalent paradoxical ideas so successfully that “atheists and Catholics, mystics and surrealists” can all find “doctrinal confirmation” in his work (Fowlie 1946, p. 39). The paradoxical nature of a character like the prince in Tale (the 3rd poem of Illuminations) who both violently destroys the genie he meets and is the genie, can be conceptually revealed through an ambiguous and metamorphosing visual form as clearly as it can be expressed poetically, and more easily than non-poetic language could express a similar idea.

There seems to be some consensus between Surrealists, Langer, and scientists that metaphor is a process for expressing and understanding new ideas, thereby increasing knowledge (Hedges 1983; Langer 1974; University of California Television 2008). Dr. Ramachandran (University of California Television 2008) describes metaphor as taking unrelated ideas and making a link using either words or pictures. He believes that metaphor is a fundamental principle of artistic “grammar” by which visual ideas are presented to us somewhere between perceptual and conceptual processing (University of California Television 2008). The “language universal” recently found by researchers at MIT suggests such linking may exist in all languages because they all create meaning by organizing associated words in close physical proximity within the sentence (O’Grady 2015). Langer (1974, p. 147) also views metaphor as central to art: “Metaphor is the law of growth of every semantic. It is not a development, but a principle.” She relates it to the “laws of imagination” and views it not as an intentional device, but as an inevitable growth resulting from “the power whereby language embraces a multimillion things; whereby new words are born and merely analogical meanings become stereotyped into literal definitions” (Langer 1967, p. 141). The meanings of words and other symbols are not static and metaphor creates “metamorphosis of its meaning,” so that words in poetry may “hover between literal and figurative,” and what begins as wild metaphor can change to almost literal meaning while carrying “a trace of every meaning it has ever had” (Langer 1974, p. 281-282). Surrealists similarly relate metaphor to their alchemical concept of metamorphosis, and they use it to combine disparate elements into poetic facts that Breton (cited in Hedges 1983) insists should be taken literally. The metaphors in Illuminations often have a literal sense that could be revealed or reinforced pictorially due to the cross-modal and pre-rational nature of metaphor. The qualities of Rimbaud’s metaphorical landscapes, for example the difference between a sea “which rose in layers above as in old engravings” and a “sea made of an eternity of hot tears” can be made apparent through pictorial techniques that take metaphorical qualities as literal and support if not express the same core poetic symbolism (trans. Ashbery 2011, p. 19, 27).

Illuminations uses the highly charged symbols of nature mythology, alchemy, religion, fairy-tale, and legend as its materials. Langer suggests that these symbols “are not bound to any particular words, nor even to language, but may be told or painted, acted or danced, without suffering distortion or degradation” (Sewell, cited in Langer 1967, p. 274). If a visual adaptation could denote these same symbols in accompaniment to the text, then the meaning of the art symbol, which is the presentation of the idea, could become more highly articulated. Images are “our readiest instruments for abstracting concepts from the tumbling stream of actual impressions” (Langer 1974, p. 145). Associated meanings are not “part of the import of poetry; they serve to expand the symbol” (Langer 1967, p. 242), and some of these associated meanings and the emotional import of iconographic symbols could be simultaneously presented through images that contain the poems. Poetry creates virtual events that are simplified in order to be more fully perceived (Langer 1967, p. 212), and images similarly simplify forms and selectively emphasize what strikes the artist as significant (Langer 1967; University of California Television 2008). A caricature can be easier to recognize than a photograph of a person because our brains are sensitive to deviations from the norm, to artistic exaggeration (University of California Television 2008; Livingstone 2002, p. 204). Symbols like rainbows, which appear numerous times in Illuminations, carry traces of multiple meanings; scientifically they are one of the most striking naturally occurring “virtual objects,” in nature mythology they are treated as elusive maidens, and in alchemy they represent rebirth with each colour being a stage in the process to spiritual perfection (Langer 1967, p. 49; Bays 1964). These meanings and more are attached to the word as well to the image of a rainbow, but only an image can symbolize a rainbow while also emphasizing the characteristic(s) of significance, whether it is the transient elusive quality, the brilliance of the hues, or the weather conditions of sun and rain that cause the illusion. Images can bring forth the sensuous character of words through representation with emphasis, what Dr. Ramachandran (University of California Television 2008) calls, “deliberate distortion for the purpose of hyperbole” and Langer (1967, p. 51) describes as abstracting physical forms to make them clearly apparent. These sensuous qualities and aesthetic surface are “in the service of its vital import” which is the emotional meaning of the art symbol (Langer 1967, p. 59).

Visual Techniques for Expansion of the Art Symbol: Vital Illusion Through Global vs. Local Pattern, and Colour

To create the art symbol in both poetry and painting:

Every element must seem at once distinct . . . and also continuous with a greater, self-sustained form . . . This integral relationship . . . produces the oft-remarked quality of “livingness” in all successful works (Langer 1967, p. 373).

The art symbol can make a “nameless passage of ‘felt life,’ knowable,” even if the viewer has not felt it (Langer 1967, 374). Understanding a work “begins with an intuition of the whole presented feeling. Contemplation then gradually reveals the complexities of the piece” (Langer 1967, p. 379). Images have the difference of presenting constituents “simultaneously, so the relations determining a visual structure are grasped in one act of vision” and the global pattern is perceived immediately, unlike the experience of reading a poem line by line and gradually perceiving the impact of the larger form (Langer 1974, p. 93). The global impact of an image can grab our attention at once and our subsequent eye movements are systematized by the attraction of our foveal vision towards the areas of high contrast and detail (Yarbus, cited in Livingstone 2002, p. 88).

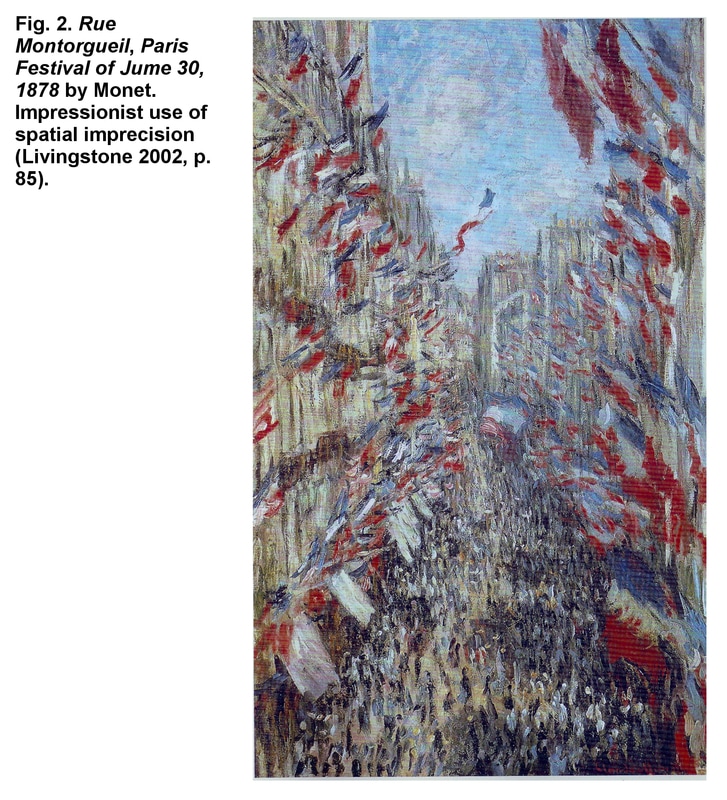

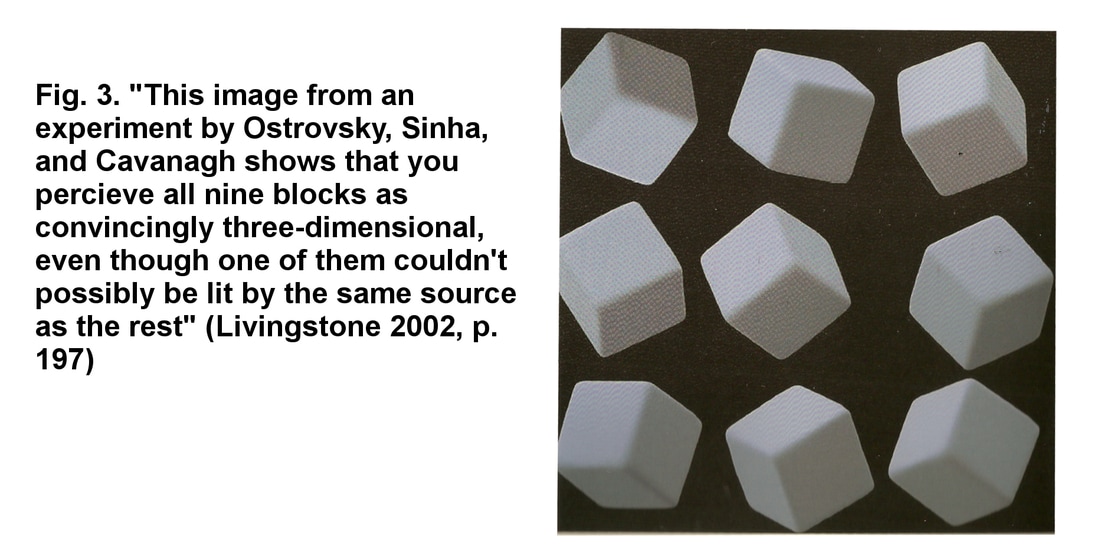

The visual interplay of global vs. local patterns in images can create a dynamic livingness because of how we see and process information. Our low visual acuity and spatial precision in peripheral vision lends vitality to images because the visual system completes it differently with each glance (Livingstone 2002). This can create a “transient feel” compatible with a “fleeting moment” (Livingstone 2002, p. 87), as seen in this spatially imprecise impressionist painting (Fig. 2). Pointillists similarly create a transient illusion by using small dots that blend into one surface within our peripheral vision, but resolve as separate to our foveal vision or local focus (Livingstone 2002, p. 110). Chuck Close extended the pointillist technique by using more complex shapes as his building blocks in the dynamic global forms of portraits (Livingstone 2002, p. 114). The facts of local and global visual processing also allow the imaginative use of depth and shading in the art symbol because our computations for perceiving 3D form and depth are made from local cues and can generate satisfying sensations without being globally consistent, as seen in this unrealistically lit cube diagram (fig. 3) (Livingstone 2002, p. 197). Dynamic painterly illusions can evoke transient memories or unrealistically lit dreams similar to the semblance of prose fiction.

Every element must seem at once distinct . . . and also continuous with a greater, self-sustained form . . . This integral relationship . . . produces the oft-remarked quality of “livingness” in all successful works (Langer 1967, p. 373).

The art symbol can make a “nameless passage of ‘felt life,’ knowable,” even if the viewer has not felt it (Langer 1967, 374). Understanding a work “begins with an intuition of the whole presented feeling. Contemplation then gradually reveals the complexities of the piece” (Langer 1967, p. 379). Images have the difference of presenting constituents “simultaneously, so the relations determining a visual structure are grasped in one act of vision” and the global pattern is perceived immediately, unlike the experience of reading a poem line by line and gradually perceiving the impact of the larger form (Langer 1974, p. 93). The global impact of an image can grab our attention at once and our subsequent eye movements are systematized by the attraction of our foveal vision towards the areas of high contrast and detail (Yarbus, cited in Livingstone 2002, p. 88).

The visual interplay of global vs. local patterns in images can create a dynamic livingness because of how we see and process information. Our low visual acuity and spatial precision in peripheral vision lends vitality to images because the visual system completes it differently with each glance (Livingstone 2002). This can create a “transient feel” compatible with a “fleeting moment” (Livingstone 2002, p. 87), as seen in this spatially imprecise impressionist painting (Fig. 2). Pointillists similarly create a transient illusion by using small dots that blend into one surface within our peripheral vision, but resolve as separate to our foveal vision or local focus (Livingstone 2002, p. 110). Chuck Close extended the pointillist technique by using more complex shapes as his building blocks in the dynamic global forms of portraits (Livingstone 2002, p. 114). The facts of local and global visual processing also allow the imaginative use of depth and shading in the art symbol because our computations for perceiving 3D form and depth are made from local cues and can generate satisfying sensations without being globally consistent, as seen in this unrealistically lit cube diagram (fig. 3) (Livingstone 2002, p. 197). Dynamic painterly illusions can evoke transient memories or unrealistically lit dreams similar to the semblance of prose fiction.

Langer (1967, p. 291) describes the prose writer as working in the “‘mnemonic mode’- like memory, only depersonalized, objectified.” Both prose poems and images can create a global pattern in the “mnemonic mode” of virtual experience (Langer 1967; Livingstone 2002). The difference is that with complex moods that can only be described by the situations that evoke them (like “village festival” or “sunset and evening star”), through an image the global semblance can be presented to perception immediately rather than built up systematically through descriptive detail (Langer 1974, p. 241). Both poems and images can exhibit the double character of elements within the global and local patterns (Langer 1967 p. 216; Livingstone 2002, ch14). For instance, a human expressing sadness may be described in a poem or shown in an image that has a global semblance of happiness or anything else (Baensch, cited in Langer 1967, p. 20). Since, as Langer (1967, p. 265) says, “the poetically created world is not limited to the impressions of one individual, but it is limited to impressions,” it follows that a visual adaptation of Illuminations could add more immediate impressions that mirror the global vs. local pattern of the poems.

May not a non -discursive symbolism of light and color, or of tone, be formulative of that [inner] life? (Langer 1974, p. 98)

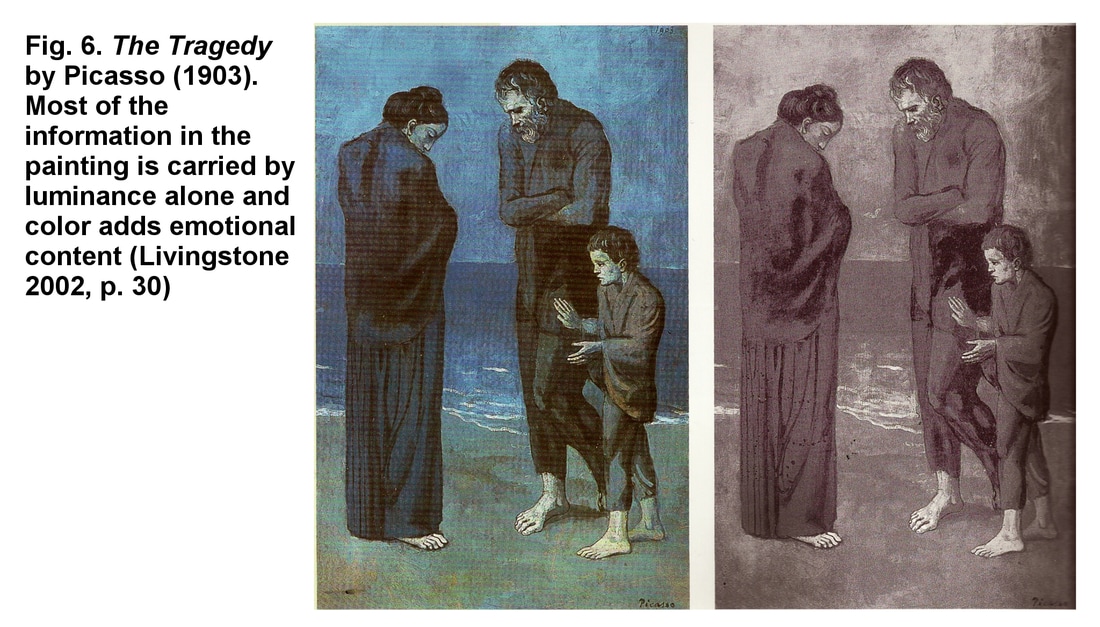

Colour is the visual element that is probably most closely related to the emotive symbolism of music, and it can similarly be utilized to qualitatively multiply the emotional content of a poem. Neurobiologist Margaret Livingstone (2002, p. 220) notes that “there are parallels between the biology of hearing and seeing,” and Langer (1967, p. 56) suggests that the emotive forms of both music and images rely on composition using data or materials that exist in some “ideal continuum - e.g. colors in a scale of hues . . . tones in a continuous scale of pitches.” The existence of hues within a circular continuum is itself an illusion, based on how our brains perceive colour (Livingstone 2002). “Color seems to form some kind of closed system perceptually” though different wavelengths of light have no physical continuity externally (Livingstone 2002, p. 63). The “existence” and impact of complimentary colours and emotionally significant colours is solely a product of the way our brains function, and visual artists can “titillate our brains more than reality” by creating illusions that exploit the way the human brain perceives colour (Livingstone 2002; University of California Television 2008). Evolution has proven lucky for the artistic use of colour because our main input for perception of three dimensionality, space, depth, movement, and spatial organization are carried out by an older “luminance only” system that is colour-blind (Livingstone 2002, p. 55). As a consequence of colour being perceived by a separate system, artists “can use any hue . . . as long as you have the appropriate luminance [value] contrast, and . . . three-dimensional shape from shading” (Livingstone 2002, p. 167). Thus biology frees colour from descriptive function and it can instead function expressively, being used “strictly to give additional poetic or symbolic meaning” (Livingstone 2002, p. 171). The Fauves and Picasso used colour this way while still employing luminance that realistically described anatomical form and space (fig. 4) (Livingstone 2002, p. 167).

May not a non -discursive symbolism of light and color, or of tone, be formulative of that [inner] life? (Langer 1974, p. 98)

Colour is the visual element that is probably most closely related to the emotive symbolism of music, and it can similarly be utilized to qualitatively multiply the emotional content of a poem. Neurobiologist Margaret Livingstone (2002, p. 220) notes that “there are parallels between the biology of hearing and seeing,” and Langer (1967, p. 56) suggests that the emotive forms of both music and images rely on composition using data or materials that exist in some “ideal continuum - e.g. colors in a scale of hues . . . tones in a continuous scale of pitches.” The existence of hues within a circular continuum is itself an illusion, based on how our brains perceive colour (Livingstone 2002). “Color seems to form some kind of closed system perceptually” though different wavelengths of light have no physical continuity externally (Livingstone 2002, p. 63). The “existence” and impact of complimentary colours and emotionally significant colours is solely a product of the way our brains function, and visual artists can “titillate our brains more than reality” by creating illusions that exploit the way the human brain perceives colour (Livingstone 2002; University of California Television 2008). Evolution has proven lucky for the artistic use of colour because our main input for perception of three dimensionality, space, depth, movement, and spatial organization are carried out by an older “luminance only” system that is colour-blind (Livingstone 2002, p. 55). As a consequence of colour being perceived by a separate system, artists “can use any hue . . . as long as you have the appropriate luminance [value] contrast, and . . . three-dimensional shape from shading” (Livingstone 2002, p. 167). Thus biology frees colour from descriptive function and it can instead function expressively, being used “strictly to give additional poetic or symbolic meaning” (Livingstone 2002, p. 171). The Fauves and Picasso used colour this way while still employing luminance that realistically described anatomical form and space (fig. 4) (Livingstone 2002, p. 167).

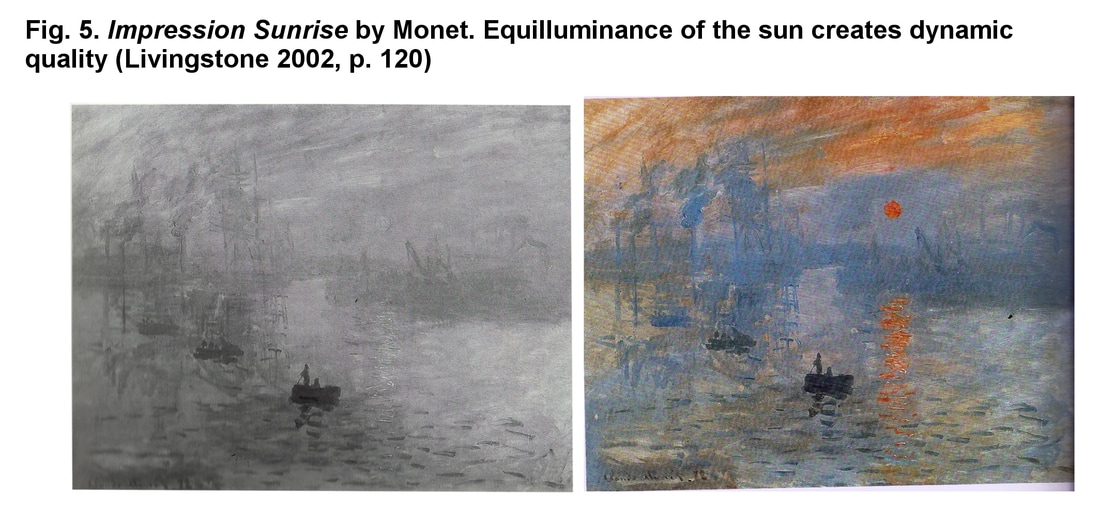

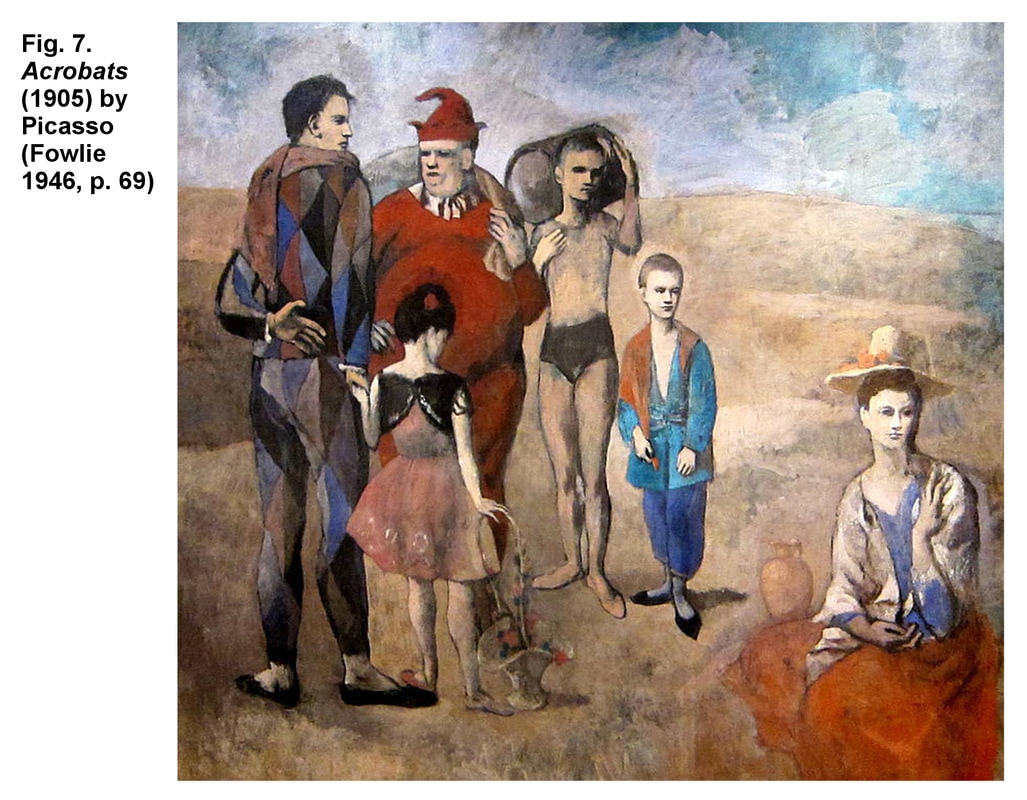

The poetic use of colour in art is complicated by the fact that our perception of colour is context dependent. The power of a colour to “advance or recede, enhance or soften or dominate other colors . . . create tension and distribute weight” (Langer 1967, p. 84) and even whether it is perceived as warm, cold, dark, or light, is based on perception of colour in relation to its immediate surround (Livingstone 2002). This makes the emotive qualities of a colour variable and open to artistic manipulation and also allows colour-based illusions that have a dynamic quality. Dr. Livingstone (2002, p. 119) has suggested that the equilluminance of Monet’s sun in Impression Sunrise is the reason that it can appear “both hot and cold, light and dark . . . [and] seems to pulsate.” It is invisible to the luminance-only part of our visual system giving us a dynamic sense of pulsating livingness (fig. 5) (Livingstone 2002, ch9). Picasso’s painting The Tragedy employs a realistic luminance range but carries the emotional content, the melancholy symbolism, through colour (fig. 6) (Livingstone 2002, p. 32). The poetic import of Picasso’s use of colour in Acrobats (fig. 7) was noted by Rilke;

Picasso has given a clear expression of his philosophy and cosmology in his painting of acrobats. And the lost landscapes of Rimbaud’s hells are the setting for his most personal experience (Fowlie 1946, p. 70).

This suggests that there is a visual world, perhaps one that emotively uses colour, which is connected to the feeling of Rimbaud’s poetic symbolism. A visual adaptation of Illuminations could make use of the poetic functions of colour and elaborate nuanced indefinable moods, as well as presenting the many named colours (violette, azur, verdure, verdigris, etc.) (trans. Ashbery 2011) for more immediate emotional perception.

Picasso has given a clear expression of his philosophy and cosmology in his painting of acrobats. And the lost landscapes of Rimbaud’s hells are the setting for his most personal experience (Fowlie 1946, p. 70).

This suggests that there is a visual world, perhaps one that emotively uses colour, which is connected to the feeling of Rimbaud’s poetic symbolism. A visual adaptation of Illuminations could make use of the poetic functions of colour and elaborate nuanced indefinable moods, as well as presenting the many named colours (violette, azur, verdure, verdigris, etc.) (trans. Ashbery 2011) for more immediate emotional perception.

Conclusion

The relation of the various arts in symbolizing the non-discursive semblance of sentience (emotion objectified) provides a context for the adaptation of Illuminations from the poetic to visual mode through images that absorb the poems as visual elements. The intended formulative power of the Rimbaudian and Surrealist use of language could be reinforced and made immediate through images that echo and support the many levels and kinds of symbols in the poetic epic. Associated meanings could be expanded and emotive qualities could be multiplied. Images could be created using techniques that exploit the way our visual system functions to create dynamic impressions of memory, movement, and poetically symbolic colour. Illuminations and other poetic works can be visually adapted because poems and images can have a similar expressive core, evidenced by the impression that Picasso's Acrobats are clearly standing in Rimbaud's Season in Hell. Nobody would mistake the setting for Whitman's Leaves of Grass.

Bibliography & References

Bays, G. (1964). Rimbaud-Father of Surrealism?. Yale French Studies, (31), p.45.

Breton, A. (1969). Manifestoes of Surrealism. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Bufford, S. (1972). Susanne Langer's Two Philosophies of Art. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 31(1), p.9.

Fowlie, W. (1946). Rimbaud. London: D. Dobson Ltd.

Fowlie, W. (1949). Rimbaud in 1949. Poetry, 75(3), pp.166-169.

Fowlie, W. (1993). Rimbaud and Jim Morrison. Durham: Duke University Press.

Hart, R. (1997). Langer's Aesthetics of Poetry. Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society, 33(1), pp.183-200.

Hedges, I. (1983). Surrealist Metaphor: Frame Theory and Componential Analysis. Poetics Today, 4(2), p.275.

Indiana University-Purdue University Fort Wayne, (2007). The Sacred and the Profane - Surrealist Poetry and the Dissolution of Dichotomy. [video] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vfMVuSSvBtc [Accessed 5 Oct. 2015].

Langer, S. (1967). Feeling and Form: A Theory of Art. 4th ed. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Limited.

Langer, S. (1974). Philosophy in a New Key. 3rd ed. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Livingstone, M. (2002). Vision and Art. New York, N.Y.: Harry N. Abrams.

O'Grady, C. (2015). MIT Claims to Have Found a "Language Universal" That Ties All Languages Together. Ars Technica UK. [online] Available at: http://arstechnica.co.uk/science/2015/08/mit-claims-to-have-found-a-language-universal-that-ties-all-languages-together/ [Accessed 5 Oct. 2015].

Reese, S. (1977). Forms of Feeling: The Aesthetic Theory of Susanne K. Langer. Music Educators Journal, 63(8), p.44.

Reichling, M. (1993). Susanne Langer’s Theory of Symbolism: An Analysis and Extension. Philosophy of Music Education Review, 1(1).

Reichling, M. (1995). Susanne Langer's Concept of Secondary Illusion in Music and Art. Journal of Aesthetic Education, 29(4), p.39.

Rimbaud, A. and Ashbery, J. (2011). Illuminations. New York: W.W. Norton.

Rimbaud, A., Léger, F. and Miller, H. (1949). Les illuminations. Lausanne: Grosclaude, Éditions des Gaules.

UC Berkeley, (2012). The Psychology of Aesthetics. [video] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UwsEeQpxkFw [Accessed 5 Oct. 2015].

University of California Television, (2008). 40/40 Vision Lecture: Neurology and the Passion for Art. [video] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0NzShMiqKgQ [Accessed 5 Oct. 2015].

Breton, A. (1969). Manifestoes of Surrealism. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Bufford, S. (1972). Susanne Langer's Two Philosophies of Art. The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 31(1), p.9.

Fowlie, W. (1946). Rimbaud. London: D. Dobson Ltd.

Fowlie, W. (1949). Rimbaud in 1949. Poetry, 75(3), pp.166-169.

Fowlie, W. (1993). Rimbaud and Jim Morrison. Durham: Duke University Press.

Hart, R. (1997). Langer's Aesthetics of Poetry. Transactions of the Charles S. Peirce Society, 33(1), pp.183-200.

Hedges, I. (1983). Surrealist Metaphor: Frame Theory and Componential Analysis. Poetics Today, 4(2), p.275.

Indiana University-Purdue University Fort Wayne, (2007). The Sacred and the Profane - Surrealist Poetry and the Dissolution of Dichotomy. [video] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vfMVuSSvBtc [Accessed 5 Oct. 2015].

Langer, S. (1967). Feeling and Form: A Theory of Art. 4th ed. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Limited.

Langer, S. (1974). Philosophy in a New Key. 3rd ed. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Livingstone, M. (2002). Vision and Art. New York, N.Y.: Harry N. Abrams.

O'Grady, C. (2015). MIT Claims to Have Found a "Language Universal" That Ties All Languages Together. Ars Technica UK. [online] Available at: http://arstechnica.co.uk/science/2015/08/mit-claims-to-have-found-a-language-universal-that-ties-all-languages-together/ [Accessed 5 Oct. 2015].

Reese, S. (1977). Forms of Feeling: The Aesthetic Theory of Susanne K. Langer. Music Educators Journal, 63(8), p.44.

Reichling, M. (1993). Susanne Langer’s Theory of Symbolism: An Analysis and Extension. Philosophy of Music Education Review, 1(1).

Reichling, M. (1995). Susanne Langer's Concept of Secondary Illusion in Music and Art. Journal of Aesthetic Education, 29(4), p.39.

Rimbaud, A. and Ashbery, J. (2011). Illuminations. New York: W.W. Norton.

Rimbaud, A., Léger, F. and Miller, H. (1949). Les illuminations. Lausanne: Grosclaude, Éditions des Gaules.

UC Berkeley, (2012). The Psychology of Aesthetics. [video] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UwsEeQpxkFw [Accessed 5 Oct. 2015].

University of California Television, (2008). 40/40 Vision Lecture: Neurology and the Passion for Art. [video] Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0NzShMiqKgQ [Accessed 5 Oct. 2015].